svc; an opinionated Go service framework

🔗 Permalink

Table of contents

I have been writing Go (or Golang) for about 6 years now. In that time I’ve seen quite a few different ways on how to organize a Go project. During my time at MessageBird I got introduced to a nice layered approach. I’ve taken those lessons and applied them to something that feels right for me; github.com/gerbenjacobs/svc

svc

svc is not an actual framework, but more a convention for creating microservices.

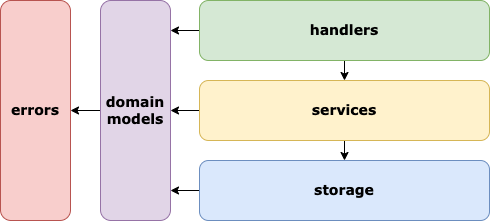

The core of svc is centered around 3 layers: handlers, services and storages.

Together with the cmd folder they are responsible for organizing your code into a clean and well-organized structure.

The idea is that requests only flow down the stack and answers flow up. These layers are connected via domain models.

Communication between the layers is done via interfaces. These are located in the file with the same name as the layer.

So in order to learn more about what kind of storages we have, for example, you can visit /storages/storage.go.

Handlers

Handler is a struct that acts as a dependency injection container. They are the entry point for your application, everything is delegated from there.

They translate your requests into domain models and delegate the actual work to services, and vice versa.

// Handler is your dependency container

type Handler struct {

mux http.Handler

Dependencies

}

// Dependencies contains all the dependencies your application and its services require

type Dependencies struct {

UserSvc services.UserService

WebhookSvc services.WebhookService

Auth *services.Auth

}

// New creates a new handler given a set of dependencies

func New(dependencies Dependencies) *Handler {

h := &Handler{

Dependencies: dependencies,

}

r := httprouter.New()

r.GET("/", redirect("health"))

r.GET("/health", health)

r.POST("/v1/user", h.createUser)

r.GET("/v1/user", h.AuthMiddleware(h.readUser))

r.GET("/v1/webhook/:webhookID", h.readWebhook)

return h

}

The actual main function of your application then creates a new Handler and passes the required dependencies to it.

In this case it’s set up as an HTTP server, but you could switch these out with GRPC for example.

// set up the route handler and server

app := handler.New(handler.Dependencies{

Auth: auth,

UserSvc: userSvc,

WebhookSvc: webhookSvc,

})

srv := &http.Server{

Addr: ":8080",

ReadTimeout: 5 * time.Second,

WriteTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

Handler: app,

}

The route that’s responsible for reading webhooks then relies on the webhook service. We know that the webhook service

replies with a Webhook model or an error and handle accordingly. In fact, we know about ErrWebhookNotFound and

can handle that differently, namely with a 404 status code.

func (h *Handler) readWebhook(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, p httprouter.Params) {

// we go into our dependency container and get the webhook service

webhook, err := h.WebhookSvc.Read(r.Context(), p.ByName("webhookID"))

switch {

// note that errors are also considered as domain models

case errors.Is(err, app.ErrWebhookNotFound):

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusNotFound)

return

case err != nil:

error500(w, err)

return

}

// custom output format for webhooks

type webhookOutput struct {

URL string `json:"url"`

Triggers []string `json:"triggers"`

TriggeredAt time.Time `json:"triggered_at"`

}

// apparently our API docs are a bit different from our local domain model

whResp := webhookOutput{

URL: webhook.URL,

Triggers: webhook.Events,

TriggeredAt: webhook.UpdatedAt,

}

if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(whResp); err != nil {

error500(w, err)

return

}

}

Services

Services are the glue between the layers. They are running the business logic of your application. This includes business validation, collecting data from the storage layer, and any kind of generating, collecting or filtering.

The file /services/service.go contains the definition of the service interface. This interface is also part of

the dependencies in the handler.

type UserService interface {

Add(ctx context.Context, user *app.User) error

User(ctx context.Context, userID uuid.UUID) (*app.User, error)

}

In the file /services/user.go you can see how the service is implemented. We can’t use the name UserService because

that’s already taken by the interface. This is also the reason I called the project svc, if I remember correctly.

// UserSvc is our service struct that implements the services.UserService interface

type UserSvc struct {

storage storage.UserStorage

auth *Auth

}

func NewUserSvc(userStorage storage.UserStorage, auth *Auth) (*UserSvc, error) {

return &UserSvc{

storage: userStorage,

auth: auth,

}, nil

}

// User returns the user based on the user ID

func (u *UserSvc) User(ctx context.Context, userID uuid.UUID) (*app.User, error) {

return u.storage.Read(ctx, userID)

}

// Add adds a user to our service and repository

func (u *UserSvc) Add(ctx context.Context, user *app.User) error {

userID := uuid.New()

token, err := u.auth.Create(userID.String())

if err != nil {

return err

}

// create user object

user.ID = userID

user.Token = token

n := time.Now().UTC()

user.CreatedAt = n

user.UpdatedAt = n

// persist it

return u.storage.Create(ctx, user)

}

Storages

Storages handle the persistence of the domain models. Sometimes these can be taken directly from the model, sometimes they need to be converted to a storage model, or DAO if you wish.

In the file /storages/storage.go we can again find the interface. Having our storages be interfaces allows us

to easily swap out the storage implementation for testing.

type UserStorage interface {

Create(ctx context.Context, user *app.User) error

Read(ctx context.Context, userID uuid.UUID) (*app.User, error)

AllUsers(ctx context.Context) []*app.User

}

It’s good to keep in mind that you’re only allowed to communicate with domain models. You can see this in action when dealing with MySQL errors, something the service should know nothing about.

func (u *UserRepository) Read(ctx context.Context, userID uuid.UUID) (*app.User, error) {

uid, _ := userID.MarshalBinary()

row := u.db.QueryRowContext(ctx, "SELECT id, name, token, createdAt, updatedAt FROM users WHERE id = ?", uid)

// Rationale: I'm reusing the app.User here because the fields are quite primitive types

// Depending on your scheme you could easily do some transformations here to change

// app.User to a customer UserDAO struct, f.e. when your database engine stores bools as tinyints.

user := new(app.User)

err := row.Scan(&user.ID, &user.Name, &user.Token, &user.CreatedAt, &user.UpdatedAt)

switch {

// Rationale: Our service layer knows nothing about sql.ErrNoRows, but we at this point do

// that's why it's important to convert your database engine errors to common Domain model errors

// that are known within the application.

// This specific example makes use of the %w verb to wrap errors with a custom message

case err == sql.ErrNoRows:

return nil, fmt.Errorf("user with ID %q not found: %w", userID, app.ErrUserNotFound)

// Rationale: Here we're explicitly not wrapping the error as the service shouldn't do anything with it.

// However, if you started noticing these in your logs, you can probably handle them like the above case.

case err != nil:

return nil, fmt.Errorf("unknown error while scanning user: %v", err)

}

return user, nil

}

Summary

If you want to get separation of concerns and clarity when developing, this is a nice convention to follow.

- Your application is divided into layers.

- Layers communicate with other layers, via interfaces, by sending and receiving domain models

- Handlers talk to services, services talk to other services and storages.

I introduced this framework successfully at Kramp Hub, and it allowed the team to easily jump between projects and quickly get started. We used GRPC so some interfaces were actually protobuf services, but other than that it still worked the same.

I’m also introducing it at GitHub with my team right now. This time however it’s a bit more difficult. The team is larger and the project is already quite large; perhaps not even micro anymore. I’ve switched from “layers with packages” to “layers in packages”. This is an ongoing process, so I might write a follow-up on that.